A new Fed study and associated workshop revealed that mortgage lenders continue to offer inflated mortgage rates to consumers, despite ongoing efforts to reduce such borrowing costs.

Over the past several years, the Fed has pledged to purchase billions in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in an effort to lower consumer mortgage rates.

The plan seems to have worked so far, pushing 30-year fixed mortgage rates from the five-percentage range to around 3.3% today.

However, Federal Reserve Bank of New York researchers Andreas Fuster and David Lucca argue that rates should be even lower.

In fact, the 30-year fixed could be closer to 2.6% if the yield declines in MBS were fully passed on to consumers.

Fat chance.

Lender Profits Clearly Rising

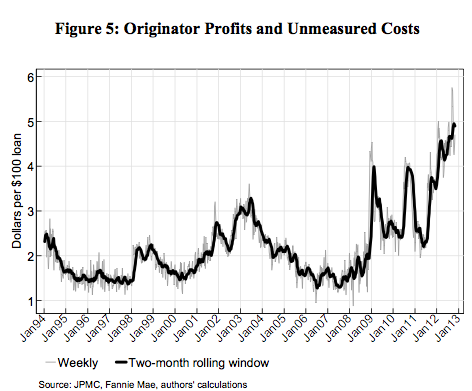

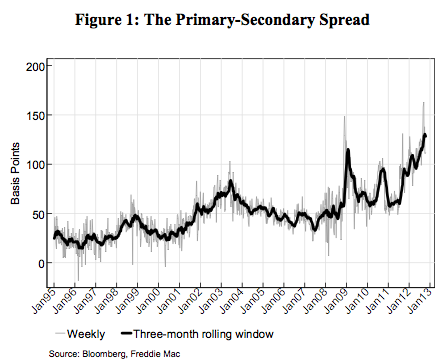

While it’s open for debate, it’s clear that lender profits have risen substantially in recent years, largely because of the widening spread between yields on MBS and primary mortgage rates.

During 2007, this primary-secondary spread was around 45 basis points, but has since risen 70 bps to about 115 bps.

Some of the participants in the workshop attributed the disparity to higher guarantee fees (which are passed on to consumers), costs associated with putback risk (repurchasing bad loans), a decline in the value of mortgage servicing rights, and so on.

But if you look at the mortgage banker profit survey from the Mortgage Bankers Association, the average profit on home loans originated in the third quarter of 2012 was $2,465, up from $1,423 two years earlier.

Profits have nearly doubled in just two years, at a time when banks and lenders have made it appear as if mortgages are no longer cash cows.

Why Won’t They Lower Mortgage Rates More?

You’d think that with profits so high, more competitors would enter the space and offer even lower rates to snag valuable market share. Or that existing lenders would battle one another and force rates lower.

Unfortunately, this hasn’t been the case. It seems as if a smaller group of large players essentially control the market.

Just look at Wells Fargo’s share of the mortgage market, which is now more than a third of total volume.

So why are things different this time around? Well, the researchers argue that lenders are increasingly uncertain about the future.

After all, this is an unprecedented time, and the recent mortgage boom could easily go bust at the drop of a hat, or perhaps at the sight of a fiscal cliff.

It’s no secret that loan origination volume is slated to fall tremendously next year, with refinances expected to slide from $1.2 trillion this year to $785 billion in 2013.

And new market entrants would probably think twice about jumping in if business is expected to slow that dramatically.

If things aren’t expected to last, taking larger profits now makes more sense, even if consumers get the short end of the stick.

Additionally, with mortgage rates already at historic lows, why go lower? I’m sure lenders are sitting back and saying, “Hey, these borrowers are already getting ridiculously low rates.”

And if all banks and lenders are in agreement, they can hold rates a bit higher than they otherwise should be.

At the same time, borrowers are probably satisfied with the rates currently available, meaning they shop less and lenders don’t have to worry about being priced out of the market.

There’s also the thought that it takes time for rates to fall on the consumer-end, as lenders get more and more comfortable with offering such a low rate.

Conversely, lenders will raise rates the second they fear they’re too low to avoid getting burned themselves.

But a more innocent explanation is simply that offering rates too low could overwhelm the banks.

Mortgage volume is already high, and staff is probably still relatively thin thanks to the recent crisis, so lowering rates more would grind things to a halt.

A lack of third-party originators, including mortgage brokers and correspondent lenders, has added to these capacity concerns.

How Low Will They Go?

The researchers summed things up by remarking that mortgage rates probably won’t fall to 2.6% in part because of the higher guarantee fees charged by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Of course, those guarantee fees should only reflect about a .25% increase in rate for the consumer. As for the remaining .50%, they argued that easing capacity constraints and thereby reducing existing lenders’ pricing power could push rates closer to a more modest 3%.

This could be accomplished by lowering net worth requirements to allow more market participants, extending rep and warranty reliefs to different servicers for streamline refinance programs, such as HARP II, and making more loans already owned by Fannie and Freddie eligible for such programs.

Ironically, the GSEs raised guarantee fees to encourage more private capital in the mortgage market, but instead it appears as if the same banks are just retaining more of the profits.