When you take out a mortgage, whether it’s a refinance or a home purchase, you may come across the phrase “cash to close.”

Virtually all mortgages require some financial contribution from the borrower to fund the loan.

It might be down payment funds, it might be lender fees, or it might be prepaid charges like property taxes and homeowners insurance.

There’s a good chance it’ll be a combination of these things, which will need to be paid at closing via a verified account.

Let’s talk more about the meaning of cash to close, how it’s calculated, and how it’s paid.

Cash to Close on a Home Loan Is More Than Just Closing Costs

If you look at your paperwork, you should see a list of closing costs associated with your home loan.

You can see estimates of these costs on both your initial Loan Estimate (LE) and also on your Closing Disclosure (CD).

And when it’s about time to close your loan, on the settlement statement prepared by your escrow officer or real estate attorney.

On these documents, you should see things like the loan origination fee, underwriting and processing fees, and other lender fees.

Additionally, there will likely be a charge for an appraisal, along with a charge for title insurance, homeowners insurance, and escrow services.

Under that escrow/title umbrella, more fees will be listed, such as courier fees, wire fees, notary fees, loan tie in fees, settlement fees, and on, and on.

There will also be recording fees and transfer taxes, along with prepaid items such as X number of months of taxes or insurance.

That’s the closing cost piece, which includes both lender fees (if applicable), and third-party fees, such as the insurance, appraisal, title/escrow.

Pretty straightforward, but we also have to consider the down payment, any deposit such as earnest money, and any seller or lender credits.

Then some math needs to be done to figure out the final amount due, which is, drumroll, the cash to close.

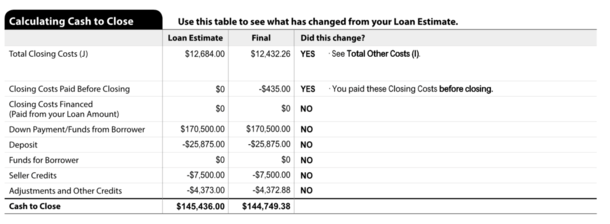

Fortunately, there’s a section on the LE and CD called “Calculating Cash to Close,” which breaks it all down for you.

How to Calculate Cash to Close: An Example

It’s probably easier to look at an example rather than keep talking about it. So check out the screenshot above, taken from a Closing Disclosure.

As you can see, it lists total closing costs, down payment funds, deposits, and credits.

In this example, the purchase price is $852,500 and the home buyer is putting down 20% to avoid mortgage insurance and get a better mortgage rate.

They’ve got $12,432.26 in closing costs, of which $435 was paid out-of-pocket before closing for an appraisal.

The borrower made a $25,875 earnest money deposit for 3% of the purchase price as well, which was originally $862,500 before a slight price reduction.

They didn’t finance any closing costs, nor did they receive any funds via the transaction.

But they did get a seller credit of $7,500 and a $4,372.88 rebate from their real estate agent.

So to tally it up, we have $182,932.26 in total costs, and $38,182.88 in credits.

That means the borrower still owes $144,749.38, which is the remaining balance after their deposit and various credits.

It covers the remaining down payment and remaining closing costs, and is typically wired to escrow at closing.

What About Cash to the Borrower?

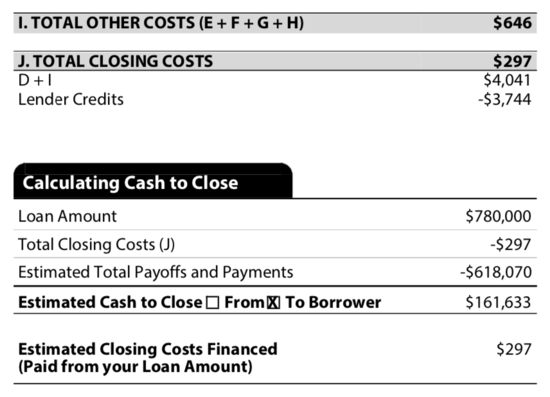

Now let’s look at a cash out refinance. In this case, there is cash going to the borrower at closing because they’re tapping their home equity.

So instead of sending money to the lender, the bank is sending money to the borrower.

In this example, the borrower also took advantage of a lender credit, which offset nearly all of their closing costs.

Their loan payoff on their existing mortgage was $618,070 and the new loan amount was $780,000.

That would send $161,930 to the borrower, but once we subtract the $297 in remaining closing costs, it’s $161,633.

Sending the Cash to Close: Some Things to Remember

When it comes time to send your cash to close funds, you’ll likely do so via wire, or possibly a cashier’s check.

Either way, the funds must come from a sourced account that was verified during the underwriting process.

For example, a bank account you verified earlier on by connecting it in the digital application or uploading monthly statements.

This way they know the money is actually coming your own funds, and not some other unverified source.

If it does come from a non-sourced account, it could delay your loan closing and cause a lot of headaches.

Remember, such funds should also be seasoned for at least two months prior as well, meaning in the account and untouched for 60+ days.

Again, this ensures the funds are your own and not someone else’s, or worse, a loan, which you deposited into your own account.

If you have questions about what is owed, it’s always helpful to speak directly with the settlement officer, who can go over everything with you line by line.

That way you know exactly what you owe, why you owe it, and most importantly, where exactly to send it.

To summarize, there are a lot of costs associated with a home loan, many of which you won’t be aware of until you go through the process yourself.

This is why it’s imperative to get a robust mortgage pre-approval and set aside funds well before beginning your home search.