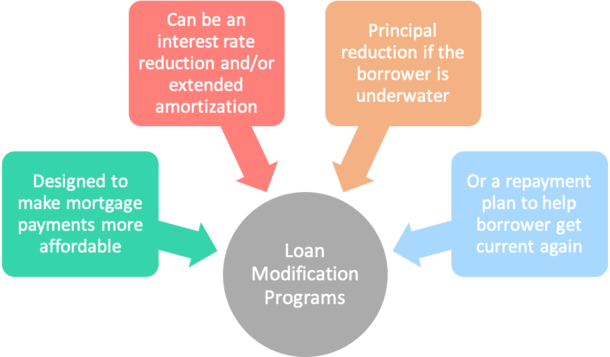

Since the mortgage crisis took flight, “loan modification programs” have become all the rage.

Instead of originating new loans, former mortgage brokers and loan officers are shifting focus to rework outstanding loans that have fallen behind in payments or are in danger of doing so.

Ironically, many are getting paid to reverse the damage they caused to begin with.

In the past couple years, millions of borrowers have fallen behind on their monthly mortgage payments, creating an unprecedented foreclosure epidemic.

And because home prices are falling, many are seeing their home equity sucked dry or even worse, finding themselves underwater on their mortgages.

This environment has forced banks and mortgage lenders to begin modifying loans in an effort to recoup losses and prevent foreclosures, which puts even more downward pressure on home prices.

Things have become so dire that a number of banks have initiated their own proprietary streamlined loan modification programs to complement their standard loss mitigation efforts.

There are also foreclosure prevention coalitions, such as Hope Now, which provide free assistance to struggling homeowners through a streamlined process using existing loss mitigation tools.

So now that we have a little background, let’s take a look at some of the most common loan modification options available to at-risk borrowers.

Mortgage Repayment Plan

- Used to get borrowers back on track if they fall behind on payments

- By adding portion of unpaid balance to monthly payments

- Until borrower is current on their home loan again

A repayment plan is one the most simple and typically most common loan workout options available to borrowers in arrears (behind on payments).

It’s not really considered a loan modification, because the terms of the loan are essentially unchanged.

Basically, the bank or lender will agree to take your delinquent payments and add them to your current monthly payments until you become current again.

So if you owe say $4,000 in arrearage, they may add $500 to your monthly payment for eight months until you’re back on track.

Critics have panned repayment plans because they fail to address the affordability issues tied to delinquent loans.

Because the debt is simply redistributed, borrowers who can’t afford the terms of their loan will likely re-default within months of receiving a repayment plan, especially as the monthly payment increases as a result.

A better option might be the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP), a government loan modification program that lowers payments based on what homeowners can afford to pay.

Interest Rate Reduction

- As the name interest rate reduction suggests

- The loan servicer or lender offers the borrower a new lower mortgage rate

- This makes the mortgage more affordable, especially if the old rate is adjustable

- New mortgage rate may be fixed for life or increase over time at a measured amount

A more favorable loan modification is one that involves an interest rate reduction, so the monthly payment is actually made more affordable.

In this case, the loan will be re-underwritten to determine what size of payment you would qualify for at a given debt-to-income ratio, generally around 38%.

The mortgage rate may be temporarily lowered, for a period of say five years, and then steadily increase, to the market rate at the time of modification, or it could be fixed for life.

This is clearly a favorable option, as it cuts the borrower’s monthly payments for good.

A common example of this is HARP, the government program that allows borrowers to refinance to a lower rate even though they lack the necessary equity typically required to do.

Extended Amortization

- Instead of lowering the interest rate

- Or providing any principal forgiveness

- The lender can simply extend the amortization period of the loan

- This can also make each monthly payment lower, though the borrower pays more interest

Another relatively easy ways for banks and lenders to increase affordability and reduce monthly mortgage payments is to extend the amortization of the loan.

Instead of a standard 30-year amortization period, the loan may be stretched another 10 years, to a 40-year term, thereby pushing payments to a more acceptable level for the borrower.

Ironically, the lender will make more money on interest over this longer time period.

Principal Reduction

- This is a less common loss mitigation tactic reserved for more serious situations

- Because banks and lenders don’t like writing off loan balances

- It’s expensive and might send the wrong message to borrowers

- But it still happens in cases where homeowners are underwater and at high risk of foreclosure

While banks and lenders aren’t generally keen to offer principal reductions, it’s becoming increasingly common as desperation grows.

Since so many borrowers are underwater, banks have little choice but to reduce the balance of the existing mortgage to put the borrower in a positive equity position and make payments affordable.

Put simply, it’s becoming a necessity when a lower interest rate coupled with a longer amortization period just isn’t enough to keep the borrower afloat.

However, there are strings attached. In exchange for a principal reduction, some banks want a piece of the future appreciation, assuming there is any.

Or they may require the borrower to keep the home for X amount of years before they’re able to sell. This has created a huge hurdle, as no one can agree on what’s fair.

Partial Claim

- Available only on FHA loans

- It results in an interest-free second mortgage

- That accounts for up to 12 missed payments

- And immediately brings the loan current

This loss mitigation method, which is only available for FHA loans, creates an interest-free second mortgage that contains up to 12 months of accrued mortgage payments.

It brings your account up to date immediately, and must be paid off in full when the first mortgage is paid off or if the property is sold.

No monthly payments are necessary, but mortgagors may voluntarily make partial payments if they wish to extinguish the claim earlier.

It’s effective because the borrower isn’t burdened with any extra cost and the lender doesn’t lose that money assuming it’s eventually paid back via a profitable home sale.

Fannie Mae HomeSaver Advance

- An unsecured personal loan

- Used to cure mortgage delinquency

- The loan is a 15-year fixed set at 5%

- With no interest or payments due during first six months

HomeSaver Advance is an unsecured personal loan, used to cure delinquency on the first mortgage. It’s a 15-year fixed-rate loan set at 5% with no interest accrual or payments for the initial six months.

The loan amount can be as much as $15,000, or 15% of the unpaid principal balance. Proceeds are applied to delinquent payments, interest, taxes, insurance, escrow advances or foreclosure/bankruptcy-related fees. No cash received in-hand.

Keep in mind that banks, lenders, and housing counseling agencies may use any combination of the above approaches to get monthly mortgage payments to acceptable levels.

For instance, it may take both extended amortization and a reduced interest rate to qualify a distressed borrower, or even principal reductions.

Also understand that some borrowers may be beyond help, as some loans underwritten over the past few years were riddled with fraud and should have never been extended to the borrowers to begin with, so foreclosure is inevitable for many.

Keep your eyes and ears open as new loan modification programs are popping up all the time. Make sure you contact your loan servicer or lender immediately if you need assistance.

One final note…watch out for loan modification scams, which seem to be becoming all the more common as the situation worsens.

Many so-called mortgage assistance programs simply create a middleman who will charge you more fees and possibly put in you an even worse position.

I cosigned for a loan in 2006. In 2014, the mortgage was modified, but I was not the one that requested the modification. The main signer and her husband signed the modification for the loan.

I was not aware that this was done. I believed they were doing a refinance to get my name out of the main loan.

They have late payments after the modification and now these show in two of my credit reports.

Since I didn’t sign the modification, is there anything I can do to get the late payments out of my credit reports?

Thanks